On November 22, 2006, Keith J. Kelly reported the

following in his "Media Ink" column of the New York Post:

A literary frenzy might soon be erupting over

a newly discovered, previously unpublished short story written by

theatrical titan Eugene O'Neill.

"The Screenews of War," one of the few short

stories he ever wrote, is believed to have been penned 90 years ago

but was quickly forgotten.

Today, at least two major magazines and a book

publisher are said to be intrigued by the 40-odd-page manuscript,

which has been quietly circulated over the past week by the

professor who made the astounding find.

The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly are

both said to be interested in the newly discovered work, according

to insiders.

Professor Robert Dowling, who teaches literature at Central

Connecticut State University, is the O'Neill buff who stumbled

across the short story. He didn't want to reveal too much about how

he located the manuscript, but says he has a clearly documented

paper trail authenticating the work.

Dowling said at least one O'Neill biographer

he contacted was aware that the story had been written, but did not

know the title or what had happened to it. "It was assumed it had

been lost," said Dowling.

On December 6, 2006, the Associated Press

reported:

A New London literary researcher has uncovered

an unpublished—and rare—short

story, written by famed playwright Eugene O'Neill.

Robert Dowling, an assistant professor of

English at Central Connecticut State University, came across the

90-year-old manuscript, "The Screenews of War," in October while

doing online research with the University of Virginia's Barrett

Library.

Most scholars thought the piece was lost or

destroyed, Dowling said.

"O'Neill was such a giant in American letters

that I just assumed this (short story) was out there, somewhere. It

really has been a slow process of gratification because it's taken a

long time to figure out what I had found," Dowling said.

Dear Professor Dowling . . .

You

have not "discovered" a missing O'Neill manuscript. The

short story was never thought to be "lost or destroyed." The

25-page typescript has been

archived in the Barrett Library at the University of Virginia for some

forty years. It is listed in their catalogue and has also been

listed as part of the Barrett Library on eOneill.com.

|

|

|

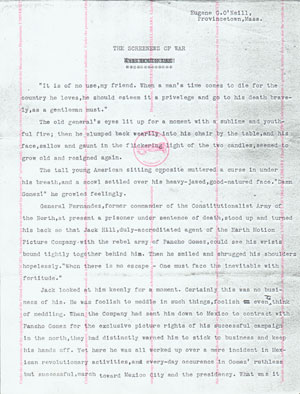

An

official University of Virginia copy of

the first page of "The Screenews of War" |

How did "Screenews" get to the University of

Virginia? The following memo was written by Harold DePolo, a

Greenwich Village friend of O'Neill's and a pulp fiction writer.

The original memo, dated January 30, 1960, accompanies the short story

at the Barrett Library.

The memo was transcribed by O'Neill biographer Louis Sheaffer, and that

transcript is part of the Sheaffer O'Neill collection at Connecticut

College.

This manuscript of THE SCREENEWS OF WAR, with

the last page missing, by Eugene G. O'Neill, was given to me in the

spring of 1918 at Provincetown, Massachusetts.

We had gone to Provincetown that season, our

first one away from a lake, to be near Gene. It was before he had

had any financial success whatsoever—just

prior to his selling his first long play, BEYOND THE HORIZON—and

he and Agnes Boulton, whom he has recently married, were living on

the ten dollars a week given Gene by his father. He told me, when he

gave me the story, that he had written it several years before and

had submitted it to some of the smooth-paper magazines, that it had

been turned down every time with printed rejection slips. Could I

possibly try to sell it for him. Whatever he could get for it would

be wonderful. I told him that, at least, I could get readings "right

from the stable," with editors who were good friends of mine and

with whom I had been dealing for year (sic). Anyway, I sent it to

Henry W. Thomas of Street and Smith and Matthew White of Munsey

Company. It didn't, alas, sell—hanged if I

know why—and when I broke the bad news to

Gene after the second throwdown he grinned and said "To hell with

it. Throw it away if you want."

I didn't. I tossed it in a drawer with some

other stuff and it has been travelling about with me, in and out of

storage, in and out of attics, ever since. There we are.

Harold DePolo was living on

reduced means by 1960 and selling everything he could,

since he had run out of people to tap for loans.

He found a willing buyer for his O'Neill manuscript in

Clifton Waller Barrett.

Desperate for money, O'Neill tried

writing short stories in 1914. He wrote "Screenews"

first as a play, "The

Movie Man," and this title can be seen X'ed out on

the first page of the story. The typescript is

headed "Provincetown," so it might have been written as

early as 1916, which would put it two years after "The

Movie Man." O'Neill biographer Arthur Gelb feels

that if the story

had shown promise, it would

have been published by George Jean Nathan and H.

L. Mencken, who had

been urging O'Neill to write stories for their magazine,

The Smart Set.

Louis Sheaffer could not have considered the story of

much importance, as he obviously knew of its existence

when he wrote his O'Neill biography (he had transcribed

the DePolo memo), yet did not mention the story in

either of his two volumes.

An

official University of Virginia copy of "The Screenews

of War" has been made available to eOneill.com by

O'Neill scholar William Davies King, who "discovered"

O'Neill's short story at the Barrett Library long before

it was "discovered" by Professor Dowling. The

O'Neill estate may allow "Screenews" to be published

on eOneill.com for anyone interested to read and

evaluate. Of course, according to insiders,

The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly are

both said to be interested in the newly discovered work!

Clearly Harley Hammerman's

"Debunking" essay demands a reply.

After finding the piece in the Virginia archives, I

carefully searched all of the O'Neill scholarship and

realized that "Screeenews" was as yet un-cited, except

under the different title "The Movie Man" in O'Neill's

work diary; and O'Neill biographers Arthur and Barbara

Gelb and Stephen A. Black acknowledge in their work that

this was probably the only short story O'Neill ever

completed other than "S.O.S." and "Tomorrow."

Thus, in his "Debunking" article, Hammerman

misrepresents the facts. He writes: "The short story was never thought to be 'lost

or destroyed.'"

In fact, Arthur Gelb wrote Hammerman himself that he

believed it was "destroyed by O'Neill," and Stephen

Black wrote me an e-mail in which he said that as far as

he knew, it was "lost"—both men used those exact words,

and Hammerman was aware of this fact. Some of the second

part of Hammerman's essay is actually taken

word-for-word from that e-mail by Arthur Gelb, which he

forwarded to me.

Hammerman also told me long into our correspondence, and

well after my efforts to get it published were underway,

that Professor William Davies King (whom I sincerely and

greatly admire) had taken notes that indicate that he

was aware of the story through Harold Depolo's memo at

the Scheaffer collection. Hammerman forwarded me the

notes, and nowhere did it demonstrate that Professor

King had read the story—this is especially clear given

the fact that "The Movie Man" is not mentioned as a

basis for it, which is not included in the memo. If

there is clear evidence that Professor King read it and

acted upon it before I did, that's one thing. Otherwise,

I don't really see Hammerman's point over all of this.

When I first heard that Professor King didn't follow-up

on this knowledge, I was a little surprised, but I

assumed he had other fish to fry with his work on Agnes

Boulton, which I very much look forward to reading.

Hammerman himself told me, after he apprised me of

Professor King's awareness of the story's existence,

that I deserved to be the first person to write about

it—but only if it's published on Laconics.

I'm not at all surprised someone else was aware of it,

as it was catalogued in the Virginia database (and

linked to eOneill.com). But

when I initially inquired about the story in October to

the archivist that handles the Barrett collection, he

wrote, "In checking the Eugene O'Neill material I did

find a typescript of a story called, 'The Screenews of

War.' Is this the story you had in mind?"

In terms of the news media semantics over the word

"discovery," the New London Day article was much more

even-handed than the Post's initial story (perhaps not

surprisingly). For example:

"Christian Dupont, director of the University of

Virginia's Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections

Library, said of Dowling, "'He's doing a great thing,

calling attention to a previously unpublished (O'Neill

short story). ... It just hadn't been noticed by

scholars all these years. What Dowling is doing is

bringing to light a well-known author's

still-unpublished work.'" Please see:

Eugene O'Neill Short Story Is Unearthed In Virginia.

"Calling attention" and "bringing to light." That's

precisely what I set out to do, but, as I'm sure most of

you agree, if the story were to be published anywhere

first, it should be in a widely read journal that the

general public might enjoy.

If it is allowed to be published first on Laconics we

will all read it, to be sure—but we would read it

anyway. By definition, as "O'Neillians"

we love and admire O'Neill and his work. If we allow it

to be published in a venue that targets the general

audience, however, then other readers, who may not have

even heard of O'Neill, might be moved to share our

deeply-felt sentiments towards America's greatest

playwright.

A colleague of mine who knows about Hammerman's desire

to get it in Laconics told me that, as a generalist and

great fan of O'Neill's, he would never encounter it if

the story was posted here. If it is published first in

Laconics, regardless of the fine work done here, it will

not gain the story's deserved attention.

In short, Hammerman has been attempting to undermine my

efforts to bring "Screenews" to the public eye since it

became clear to him that I hoped to publish the story

with my introductory essay in a place with a broader

audience than his Laconics. (Hammerman offered me money

to publish it with Laconics when he first heard about it

in the Post.) His last missive to me of December 9, in

particular, was openly hostile and foul-mouthed.

I'm terribly sorry he brought you all into this. I can

only imagine what O'Neill would think. . .

Robert M. Dowling

Assistant Professor

Department of English

Central Connecticut State University

When I first read about

Professor Dowling’s discovery in the New York Post,

I did indeed contact him and ask him if he’d be

interested in publishing the short story on eOneill.com.

At that time, I had no idea he had “discovered” a story

that had been archived and available at a university

library for quite some time.

Subsequently, Professor Dowling asked

rhetorically of me in an email, “Do you think I found it

in my grandmother's basement?” Naively, I suppose I did.

It’s not clear to me why Professor Dowling was initially

secretive about where he had “discovered” the story,

allowing my collector’s mind to wander to his

grandmother’s basement. Professor Dowling confirmed his

lack of candor in our correspondence when he said, “I

don't think you understand how I found it (naturally,

since I haven't really told anyone).” It was Professor

King who alerted me to the fact that “The Screenews of

War” was catalogued at the Barrett Library. But even

then, we both assumed that Professor Dowling had

discovered another version of the short story, or at

least another copy. It wasn’t until after I had passed

on Professor King’s information, that Professor Dowling

informed me his “discovery” was indeed the University of

Virginia manuscript. And it wasn’t until several days

later that Professor King realized he had in his

possession a copy of the story. (He had copied it

because Agnes Boulton also wrote stories set in Mexico,

and he wondered if there might be some connection.)

I am all for getting Eugene O’Neill all the publicity we

can—that’s what eOneill.com is all about. But I believe

that this publicity must be above board and professional. The

hoopla and half-truths that have surrounded Professor

Dowling’s pronouncement of his “discovery” via the press

have not met these criteria. This was not about getting

publicity for Eugene O’Neill. To once again quote

Professor Dowling’s email, “Prestige, on the other

hand—and here's where it's both existential and

psychological—is enormously important for any writer.

The more you get, the more you're heard. How's that for

a cynical bitter truth?”

Harley Hammerman

The question

of what constitutes a "discovery," as raised here by

Harley Hammerman, is an interesting one. The fact that

this unpublished short story has, so far, not been

listed (to my knowledge) in any bibliography or

reference work on O'Neill does mean that it has been

officially overlooked, but the fact remains that this

work has been "looked over" by several, and so it does

not come out of nowhere.

Aside from the fact that Barrett, then the University of

Virginia Library, catalogued it nearly half a century

ago, the evidence of Sheaffer's transcript of DePolo's

memo shows that he was aware of it. Though the Gelbs do

not mention the story's title, they state that The Movie

Man had been adapted as a short story, and they surely

reviewed all the materials in the Barrett Collection, so

presumably they, too, had seen it. How else would they

know that the one-act had been adapted at all?

I'm sure that many other O'Neill scholars have made the

journey to the beautiful campus of the University of

Virginia to look at the O'Neill materials there. Much of

what Barrett acquired came from Agnes Boulton, Harold

DePolo, and others, around 1960, who were cashing in

their O'Neill holdings at a moment when prices were

rising. The "O'Neill revival" of the late 1950s was not

just about new productions of his plays.

So, the "Screenews" (I keep wanting to put a second N in

there) surfaced. Vying for the least interesting

document of all time, this incomplete typescript shows

O'Neill (?) expanding and novelizing his uninteresting

and "lost" play from 1914, "The Movie Man." The

copyright division of the Library of Congress

successfully preserved for us this tone-deaf effort at

satire by a writer who was still trying to figure out

whether he wanted to be Joseph Conrad or Ring Lardner

(both admirable goals, both miles away).

Everyone who has looked at the whole sweep of O'Neill's

career has labored to find a place for "The Movie Man."

O'Neill appears to depict John Reed at a moment before

he knew John Reed. He reaches for atmospheric effect in

his evocation of comical Mexican speech: "'Carramba!'

Gomez shouted 'What ees eet? Ees that hombre gone crazee?'"

He depicts the crass Hollywood exploiters of Pancho

Villa as demeanors of the "peons" and "greasers."

Where are Yank and Driscoll when you need them?

The playwright, instead, is insisting upon the humor of

a revolutionary leader being told that he must fight his

battle by daylight so that the cameras can capture the

action.

It is tawdry writing at best. A young writer will

sometimes go that way. O'Neill did. However, at a

certain point, he decided he would not. A good question

is when that happened. My study of his marriage to Agnes

Boulton, who was a writer who had few illusions about

the costs and especially benefits of aiming for a

popular audience. My book on her will show that the

issue remained open for O'Neill for perhaps longer than

critics and biographers have thought up to this point.

Still, O'Neill had determined, long before he ever knew

Agnes Boulton, that he would not sell himself short, and

"The Movie Man" from 1914 already seems an anomaly. Why,

then, would he have returned to this work in 1916 or

thereafter? "Desperate for money" is a readily available

phrase, and perhaps it is apt. Perhaps O'Neill thought

it would be worth the hours of rewriting and retyping to

turn his unsuccessful play into a money-making story.

Perhaps.

But maybe not. Here I enter into the realm of pure

speculation.

The story resurfaces in 1960, in the hands of Harold

DePolo, who would die just a few months later. DePolo

had been a "pulp fiction" phenom, a man who claimed he

could write sometimes two, three, four stories in a day

back then. (See the EO Review article on DePolo by

Richard Eaton and Madeline Smith.)

DePolo did not publish much in the "smooth paper"

magazines. He was expert in the pulps, and I would guess

that a dedicated hunter of the Library of Congress pulp

files might find 300-500 stories by DePolo, from the

early 1910s through the 1920s. His star seems to have

fallen thereafter.

Sheaffer's interviews of DePolo, from the late 1950s, do

not touch on the very first encounter of DePolo and

O'Neill, but it might well have been as early as 1914,

or even 1913. As early as April of 1914 (and possibly

earlier), DePolo was publishing stories about Mexico

("The Woman I Knew," Snappy Stories, 7:3 (April 1914)).

As I was digging out pulp stories by Agnes Boulton,

scrolling through reel after reel of microfilm, I kept

bumping into DePolo stories. Some of these I copied,

randomly, usually only because I liked the title. I

managed, by this entirely undisciplined process, to

amass at least six stories written by DePolo between

1914 and 1918 set in Mexico.

Here I make a leap, in the laconic way. Is it not

possible that DePolo himself, either in 1916 or in 1918,

adapted O'Neill's measly little play from 1914,

rightfully "lost," and tried to sell it to the pulps?

The story is a mess tonally, reflecting NO sense of the

gravity of war or the humanity of its characters.

Instead, they act out emotionally disconnected points of

view on a dramatic action which is elsewhere. I suppose

you get a "wry" view of the peculiar imperialism that

Hollywood came to represent, and you get some

atmospheric dialect, but the whole effort to novelize

the play's action is so labored, so verbally plumped, it

is hard to believe that the O'Neill who was working on

"The Moon of the Caribbees" would have wasted a week on

it.

Stranger things have happened in a writer's life. Maybe

he did. However, I think it is worth considering whether

the whole business might not have been promulgated by

Harold DePolo, who had no known standard below which he

would not descend. He could not have brought forward

(for sale) his own reworking of O'Neill before O'Neill's

death because O'Neill would repudiate it. Afterward,

however, he would face no obstacle to claiming O'Neill's

authorship of something he had perhaps written.

DePolo insisted to Sheaffer that he had written the

final paragraph of O'Neill's verified short story,

Tomorrow, after the editors had asked for some revision.

He told Sheaffer to look at the different typeface of

that section. It might be interesting to compare that

typeface with the one used for this "O'Neill" story.

Then, too, the short story is filled with trivial

writing errors, "it's" for "its" and "their's" and that

sort of thing. Does that sort of error match with

O'Neill's other early writings? The idiom, too, would be

worth a look. DePolo's stories show a lot of use of

terms like "peon" and "Greaser." Are there other verbal

analogues between "Screenews" and DePolo's stories.

Finally, I wonder why he (they?) chose to change the

title from "The Movie Man" to "The Screenews of War." Am

I wrong in thinking that the latter is truly a terrible

title? From a writer (O'Neill) who was already coming up

with some of the best titles ever for plays, it is hard

to imagine him adopting this one. Another DePolo touch?

perhaps an effort to steer attention away from his

pirating of O'Neill's work?

I offer all this in the spirit of open discussion of a

topic of minor fascination.

William Davies King

Professor and Graduate Advisor

Department of Theater and

Dance

University of California, Santa Barbara

Mr.

Hammerman,

I'm not sure I understand why - if this short story was known about -

why you or Mr. King did not previously bring this to light.

It sounds to me like you are

bitter that the professor from Connecticut DID SOMETHING with the story, i.e. - tried to bring attention to it - whereas you either did nothing

(which is unthinkable, given that you run a Eugene O'Neill site), or

that you were "scooped'' and this is sour grapes.

Please show me if and

exactly how I'm wrong.

Thank you

Chris David

Harold

DePolo is my Grandfather on my mother's side. I have

several letters written / typed by him to my mother. And

I am offended by some of the things that are said about

my Grandfather. He was very loving and kind man.

Melissa Adkinson

(CONTENTS)