|

Chapter II

Life on the Jersey shore was lively, with four exuberant

daughters to keep both Ted and Cecil quite busy. Decades later, Budgie

(my mother, Margery) told me of times the girls spent on a little

sailboat named the Teddy Bear. In teenage years, their summer days on

the Manasquan River were delightful, with many friends, boat racing and

general good times The ocean just two miles away offered other

adventures. They swam, played, ran in the sand and fished with their

father. On shopping days, transportation was a small horse and an open

wagon. Winters were mild with enough snow for sledding and ice ponds for

skating. The woods on all sides were filled with holly trees covered

with deep green, thorny leaves and bright red berries.

|

|

The four Boulton daughters,

1904. |

|

|

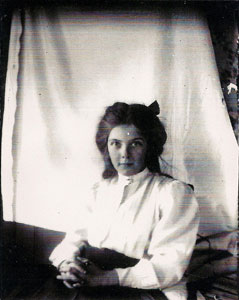

| Margery

Boulton, 1904. |

Agnes

Boulton, 1904. |

The girls adored their father and lovingly called him

Teddy. They helped with chores, feeding chickens and carrying wood. They

laughed with Ted over his funny stories and jokes and were amused with

the catchy jingles he sang. They saw a cheerful man who seemed fulfilled

with his art, his family and many friends.

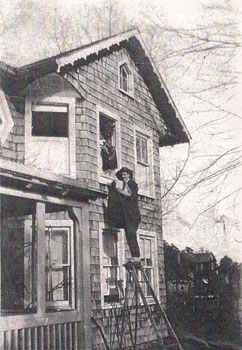

At one point, Ted and Cecil decided they needed more

space for this large family. Ted designed an extension with two large

rooms, one over the other, at the east end of the house, and had them

built by a man named Frank Bennett. The lower room became the nursery

and the upstairs was the master bedroom. The rooms were still called the

nursery and master bedroom when Oona and I were growing up. Each of the

large rooms had five windows bringing in the bright morning sun. Later

on, the upper room became Aggie’s bedroom and study where she wrote, and

the lower room became a playroom-bedroom for Oona.

|

|

|

Ted having fun on the new wing

of Old House, 1890s. |

On the back of the house Ted had included a spacious

studio with a corner for his easel, and wall space for the paintings as

he finished them. For all the years we were growing up there, his spirit

seemed to always be in that room, with the north light coming in through

a huge skylight on the roof. As children, Oona and I loved being in

there more than any other room in the house. We would listen to records,

dance and sing, play games and read, sitting on the puffy, comfortable

couch that took up part of one wall. Teddy’s easel remained, standing in

the corner.

Ted or Edward W. Boulton, a prolific artist best known

for his impressionist landscapes, had also gained a reputation for

exquisite miniature portraits. We know of only two remaining. One is of

his daughter Agnes as a young woman. Agnes' granddaughter, Victoria

Chaplin Théirrée, has it in her home in France. The other, a picture of

Cecil, remains with her great grand-daughter, Maura O’Neill Jones.

|

Miniature of

Cecil, 1890s. Photographer E.W. Boulton. |

Weekends in the early 1900s often brought Thomas Eakins

and several students from the Philadelphia Art Students League to the

Jersey shore to visit with Cecil and Ted. They rode bicycles over the

dirt roads, on the long trip across Jersey.

After the group settled themselves in at The Old House

they might pitch in to help Ted with one project or another. One such

time was when he was putting up a windmill to pump water. There were

many laughs as they struggled awkwardly to raise the giant flaps on the

ungainly structure. There was much pushing and pulling until finally the

test came and it worked! They cheered, watching the wind catch the

clumsy paddles as they began to turn. The old windmill stood for many

years, bringing fresh, cool water into the house, while the family

enjoyed hearing the great, creaking paddles catch in the wind.

Weekend evening dinners with those close friends were

invariably followed by folksongs and tunes played on a banjo, guitar or

ukulele. Teddy strummed on the guitar and might start a round of sea

chanteys or a few bawdy ballads. Young Cecil liked sitting in and

learning the words to sing along. In later years, as an adult, she

thought it fun to shock family and friends by recalling a verse or two

of what she called “the naughty songs.” It was even more delightful

because of her innocent expression.

Agnes, in a letter to Oona, told an amusing, but

distressing, story about Frank Bennett when he felt that grandfather Ted

was having a little financial trouble and

wanted to help. He thought perhaps he and Ted could raise cocks for

fighting and enter them in some of the local cock fights. Agnes wrote:

“Frank arrived late one night, his fingers on his lips, carrying a

burlap bag in which he had a beautiful and expensive cock that he had

purchased that day at a poultry show. He put it on the dining room table

and I remember we children hanging over the stairs, listening to the

whispering and Frank's excited steps. We could see it there, very

ruffled and annoyed, but bewildered in the kerosene lamplight. My poor

father did not know what to do, and for the night put the bird inside

the chicken yard, thinking no doubt, it would be safe until morning when

he could build it a pen. Going out there about six in the morning, he

told us he found only the game cock, defiantly walking about, surrounded

by dead bodies. The cock had destroyed every chicken, hens and all,

about thirty of them. Either during the night, or when dawn broke, this

proud rooster had found himself in the barnyard of common white

leghorns. Not a sound was ever heard either, so nothing ever came of

making money with this game cock. And that ended that.” The family knew

that Ted couldn't really bring himself to take such a beautiful bird to

a cock fight!

Frank Bennett also helped Ted to build a small studio,

and another house called “The House in the Woods” and the family found

themselves living in one or another of the three houses. No one really

knew why. The House in the Woods was eventually sold for $800 and rolled

on rollers down the Herbertsville Road passing The Old House and the

studio on the way. Two blocks down the road it became known as The

Antique Shoppe.

Mother Cecil was one who allowed herself to be a

caretaker, not only of everyone in the immediate family, but also of

their children in later years. She was known in West Point Pleasant for

her kindness, and became the self-appointed local midwife. When a young

neighbor was about to give birth, Cecil would trudge down the road with

her small leather bag, staying all night if necessary. She also took

turns helping those who were ill.

Cecil, though being a caretaker above everything, often

longed for a time to write poetry, and to study whatever was available

about theosophy. She had been stimulated by her mother’s interest in

these subjects. I found, later on, old notebooks with poetry and

philosophical musings jotted down from long years before. She often

walked around the house reciting poetry in French or English which duly

impressed us all. Cecil spoke French fluently and played the piano,

singing in a deep, rich voice as she accompanied herself. These were the

times she seemed most happy.

Agnes Ruby Boulton, as a small child, had been sent to a

parochial school in Philadelphia. Her mother, having become enamored

with the Catholic Church when she was living in Philadelphia, had

promised that Agnes would go to the school for part of her childhood.

After the family moved to New Jersey, Agnes in her teens, returned to

the city to study art. She quickly learned that art was not her calling,

and it wasn’t long before she decided the most important creative

activity for her was writing. She went home to West Point Pleasant again

and spent months working on this new venture. Eventually she began

taking trips to New York City to find publishers who might be interested

in her work.

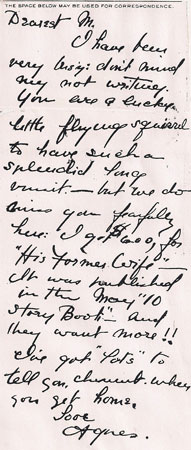

It was 1908 and Agnes was only sixteen when she

submitted a story to a popular magazine. It was accepted and published,

and this seemed the most exciting moment of her life. She had sold it to

The Smart Set, a literary magazine published by George Jean Nathan and H.L. Mencken, and immediately she wrote and submitted a second, as the

family cheered her on.

|

|

|

|

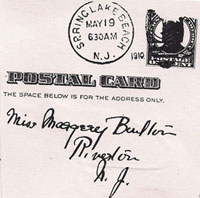

Postcard to Margery from

Agnes. Agnes at age 16, 1908. |

Agnes sold more stories to The Smart Set and to several

pulp papers and magazines, including one of the Frank Munsey*

newspapers. Her sister, Margery saved this one for eighty years and

passed it on to me to share with the rest of the family.

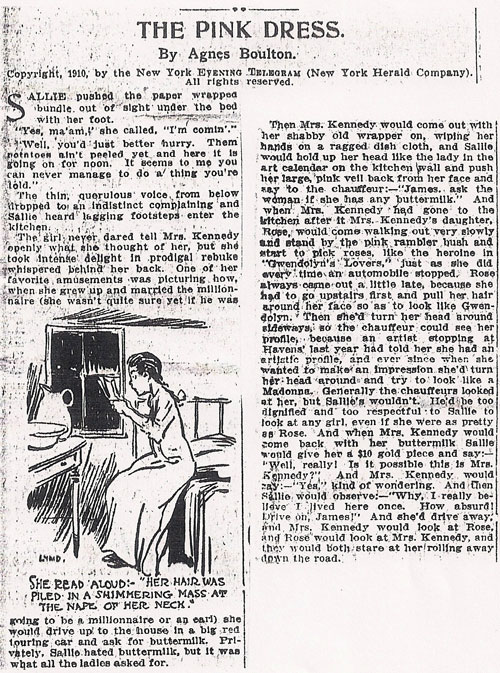

|

| “The Pink

Dress” (partial) by Agnes Boulton, New York Evening

Telegram, 1910. |

When one of Teddy's Philadelphia aunts died, Agnes found herself with an

unexpected inheritance. She had been named for her great aunt Agnes and

at age twenty-one a small amount of money and some prized furniture were

left to her. Ted and Cecil were in financial trouble and Agnes bought

The Old House to help them through this difficult period. Agnes lived in

the city a great deal of the time, while Ted and Cecil continued to stay

in The Old House in West Point Pleasant where they rightly felt most at

home.

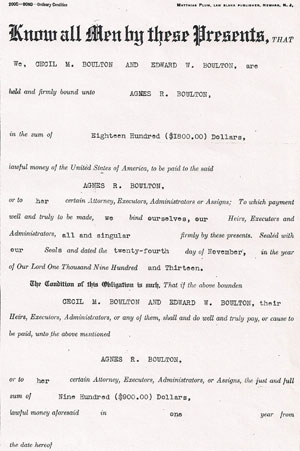

|

Deed to The

Old House from Boultons to Agnes, 1913. |

*Frank Munsey was a

well-known newspaper publisher who presented The Sun in 1916,

followed by The Evening Mail, The Evening Telegram, and

The New Evening Sun. He was considered the greatest newspaper

magnate of his day.

Chapter III

Chapter III |