By BEN BRANTLEY

The

fallen emperor has been returned to glory.

It’s not that things turn out any happier for the ill-fated title

character of Eugene O’Neill’s “Emperor Jones,” as the last hours of

his life are played out at the Irish Repertory Theater, where Ciarán

O’Reilly’s inspired revival opened Sunday night, starring a wondrous

John Douglas Thompson.

|

|

|

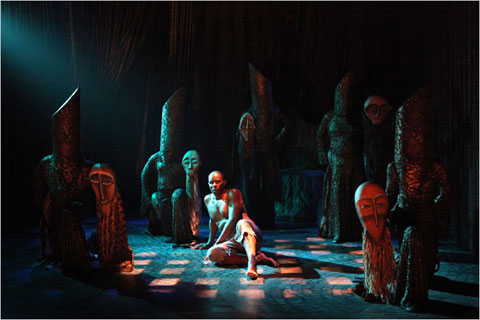

John

Douglas Thompson plays the title role in Eugene O’Neill's

"The Emperor Jones." |

Once

again Brutus Jones, the African-American island despot, is cruelly

and systematically stripped of his majesty, his dignity and all the

finer traits that separate man from beast. But in the play that

bears his name, an ember of real magnificence has been uncovered and

fanned, gently and artfully, into a blazing flame.

Set in a fluid, shadowy dreamscape, through which Mr. Thompson moves

like a thrashing sleeper in a nightmare, this “Emperor” digs into

recesses of the every-mind, setting off Jungian echoes of universal

resonance in a work often perceived as a dated portrait of the black

man’s burden. While much of Mr. O’Reilly’s production occurs in

near-darkness, I can’t think of another show (in what has been a

mostly lusterless theater season) that burns brighter.

This act of illumination is a pinnacle in the rethinking of

O’Neill’s short, brutal play, which spent decades moldering in that

corner cupboard reserved for embarrassing works by great writers.

Though it electrified New Yorkers (including Alexander Woollcott of

The New York Times) when it opened in 1920, “The Emperor Jones” came

to seem shocking for all the wrong reasons in later years.

|

|

|

John Douglas Thompson in

O’Neill’s “Emperor Jones,” directed by Ciarán O’Reilly. |

Here, after all, was a portrait of an African-American man who,

briefly endowed with power, was forced to crawl backward through the

phases of civilization, talking all the while in the thick “sho’

nuff” dialect of minstrel shows. When the avant-garde Wooster Group

performed the piece in the 1990s, a white actress (the superb Kate

Valk) played Jones in blackface. And the production became a

stinging depiction of black culture perceived through a white

world’s distorting, contemptuous and uneasy gaze.

I thought that the Wooster Group’s fiercely articulate

interpretation might be the last word on “The Emperor Jones.” Then I

saw Thea Sharrock’s fine, confrontational production at the Gate

Theater in London in 2005. (It later transferred to the National.)

Set in a sand-floored box that suggested a safari hunter’s pit for

big game, this “Emperor Jones” (starring Paterson Joseph) was played

with great anger and no irony. It exuded the painful desperation of

a man ensnared like a hounded animal, twisting in a trap forged by

years of repressive history.

Ms. Sharrock’s version invested “The Emperor Jones” with a visceral

immediacy that suggested the upsetting impact it must have had in

the 1920s. Mr. O’Reilly’s interpretation retains that charge of

power, but also elicits the poetry and haunting musicality in

O’Neill’s text.

Making exquisite use of dreamlike masks and puppets (by Bob

Flanagan) and an aural backdrop (by Ryan Rumery and Christian

Frederickson) that seems to originate in your own head, this

“Emperor Jones” is quieter and stealthier than any I’ve seen. Its

eerily lowered voice makes the case for the play as a study in the

black hole of unconsciousness (a subject just entering the

mainstream conversation in the era when it was written, and one that

fascinated O’Neill).

A shivery whisper runs through this production as Jones, a former

railroad porter and convict, descends into primal fear: It says that

the wall between human reason and animal instinct is far frailer

than we like to pretend. This tin-pot emperor, forced to retreat

into the jungle when his subjects rise up against him, is no

sociological specimen. He becomes what we’re all scared of turning

into, when adrenaline floods us in moments of raw anger or terror.

That’s partly because Mr. Thompson makes it impossible not to

identify with Jones. An impressive Othello last season (both for

Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Mass., and Theater for a New

Audience in New York), this brawny actor has a naturally commanding

physical presence, with a rich baritone voice to match. But these

assets are only a small part of what makes his Jones so compelling.

This Emperor is from the beginning a figure of subtly mixed,

potentially explosive elements, kept in tenuous balance. Like any

successful ruler, of a business or a country, he’s smart enough to

know that power is largely a matter of show. “Ain’t a man’s talkin’

big what makes him big— long as he makes folks believe it?” Jones

asks Smithers (the excellent Rick Foucheux), his Cockney henchman,

in the opening scene.

But there’s apprehension within this self-awareness, the sense that

Jones’s isn’t always comfortable in his grand, imperial postures.

His anger comes too quickly, and when he cracks his whip for show (a

motif with a harrowing echo in a later scene), you feel he’s losing

control. This is a man daunted as well as delighted by the outsize

shadow he casts, and he reminds us that recent history is full of

examples of tyrants made freakish by power.

As Jones divests himself by degrees of his crown, his boots and his

shirt, Mr. Thompson seems to go even further, showing us the skull

beneath the skin and the furiously beating heart within the rib

cage. In the reading, the late sections of the play can seem

painfully allegorical, as Jones is confronted by specters not only

of his own criminal past but also of a collective cultural past that

embraces a slave auction and mystical tribal ceremonies.

But the forms that Mr. O’Reilly and his creative team give these

phantoms, including an early set of apparitions identified in the

script as “little formless fears,” have the disturbing beauty—and

internal logic—of a symbolist painting.

Every aspect of design—Charlie Corcoran’s set and Antonia

Ford-Roberts’s costumes, Brian Nason’s transfiguring lighting and

Mr. Flanagan’s living puppets—feeds into a complete vision of

interior doubts erupting into a dominating external life. By the end

of Jones’s journey he is beyond controlling even his physical

movements, a process reflected with anguished precision in Barry

McNabb’s enriching choreography.

I don’t want to be too specific about the visions that this

production conjures up as we follow Jones, almost against our will,

into dementia. They surprised and rattled me, and I imagine they’ll

have the same effect on you. But let me say that though I’d never

thought of it before, “The Emperor Jones” turns out to be a perfect

Halloween entertainment for grown-ups. As this magical production

makes clear, O’Neill, a man of many demons, understood all too well

that everyone is his own boogeyman.